You're Speaking My Landscape, Baby.

No, that isn’t a typo… but yes, it is a bad play on words. That’s the bad news. The good news: finally! A Clockwork Aphid implementation post!

If you’re building something which relates in some way to virtual worlds, then the first thing you’re going to need is a virtual world. This gives you two options:

- Use a ready made one;

- Roll your own.

Option 1 is a possibility, and one that I’m going to come back to, but for now let’s think about option 2. So then, when building a virtual world the first thing you need is the lanscape. Once again you have two options, and let me just cut this short and say that I’m taking the second one. I did used to be a bit of a CAD ninja in a previous job, but I’m not a 3D modeller and I have no desire to build the landscape by hand.

So I’m going to generate one procedurally. As to what that means exactly, if you don’t already know… well I’m hoping that will become obvious as I go along.

Traditional Fractal Landscape Generation

There are several ways of generating a landscape. A pretty good one (and one I’m quite familiar with, thanks to a certain first year computer science assignment) is the fractal method. It goes something like this:

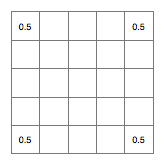

Start off with a square grid of floating point numbers, the length of whose sides are a power of two plus one. I’m going to use a 5*5 (2*2 + 1) grid for the purposes of this explanation.

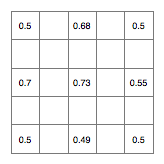

Set the four corners to have the value 0.5 (the centre point of the range I’ll be using), thus:

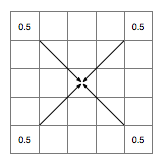

Now, we’re going to generate the landscape by repeatedly subdividing this and introducing fractal randomness (random fractility?) using the diamond square algorithm. First the diamond step, which in this iteration will the set the value of the central cell based on the value of the four corners:

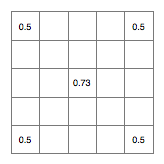

To do this we take the average of the four corners (which I calculate to be 0.5 in this case, because I did maths at school) and adding a small randomly generated offset, which has been scaled according to the size of the subdivision we’re making. How exactly you do this varies between implementations, but a good simple way of doing it is use a random number in the range [-0.25,0.25] at this stage and half this at each subsequent iteration. So, on this occasion let’s say I roll the dice and come up with 0.23. This now leaves us with:

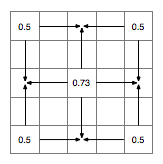

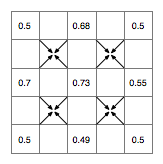

Next, we have the square step, will set the cells in the centre of each of the sides. Once again we take the averages of other cells as starting point, this time in the following pattern:

Now we generate more random numbers in the same range and use them to offset the average values, giving us this:

That completes an iteration of the algorithm. Next we half the size of the range to [-0.125,0.125] and start again with the diamond step:

…and so on until you’ve filled your grid. I think you get the general idea. I’ve left out one potentially important factor here and that’s “roughness,” which is an extra control you can use to adjust the appearance of the landscape. I’m going to come back to that in a later post, because (hopefully) I have a little more that I want to say about it. I need to play with it some more first, though.

Once you’ve finished here you can do a couple of different things if you want to actually look at your creation. The simplest is to pick a threshold value and call this “sea level,” then draw the grid as an image with pixels set to blue below the threshold and green above it:

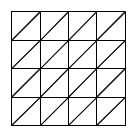

This was obviously generated with a slightly larger grid (513*513), but as you can see it creates quite reasonable coastlines. You can do slightly fancier things with it, such as more in depth colouring schemes and 3D display. For 3D, the simplest method is to use each cell as a vertex in your 3D space and tessellate the grid into triangles like this:

You can then do a couple of fancy things to remove the triangles you don’t need, either based on the amount of detail they actually add or their distance from the user (level of detail).

This system works quite well, but tends to produce quite regular landscapes, without of the variation we’re used to or the things generated by rivers, differing geology, coastal erosion, glaciation and other forces which affect the landscape of the real world. Additionally, because the data is stored in a height map, there are some things it’s just not capable of displaying, such as shear cliffs, overhangs, and cave systems. The grid structure is also very efficient, but quite inflexible.

How I’m Doing it

Needless to say that’s not exactly how I’m doing it. Of course there’s generally very little sense in reinventing the wheel, but sometimes it’s fun to try.

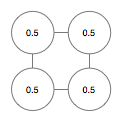

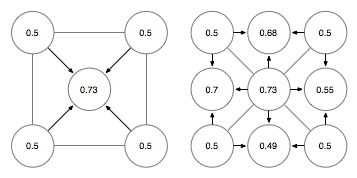

I’m not doing too much differently with the actual algorithm, but I am using a slightly different data representation. Rather than a grid, I’m using discrete nodes. So you start off with something like this:

Which then is transformed like this to generate the actual landscape:

What you you can’t see from the diagrams is that I’m using fractions to address the individual nodes. So, for instance, the node in the centre is (1/2,1/2) and the node on the centre right is (1/1, 1/2). This means I don’t need to worry about how many nodes I have in the landscape, and the adress of each never has to change. The next set of nodes will be addressed using fractions with 4 as the denominator, then 8, 16 and so on. Before looking up a node you first reduce its coordinates down to a lowest common denominator (which is a factor of 2) and then pull it out of the correct layer. I’m currently using maps as sparse arrays to store the data in a structure which looks like this:

Map<int, Map<int, Map<int, LandscapeNode>

If you’re thinking that this isn’t possible in Java, you’re half right. I’m actually using one of these. The first int addresses the denominator, then the east numerator, then the north numerator. I’ve looked at another couple of strategies for hashing the three ints together to locate a unique node but this one seems to work the best in terms of speed and memory usage. I might look at other options later, but nor yet.

This is a much more flexible representation, which removes some of the limitations of the grid. I can keep adding more detail to my heart’s content (up to a point) and I don’t have do it in a regular fashion. i.e. the native level of detail doesn’t have to be the same across the entire map. More remote areas can have less detail, for instance. By the same token, I can keep the entire “landscape” in memory, but flexibly pull individual nodes in or out depending on where the user actually is in the world, saving memory. This also potentially gives me the following:

- The possibility to decouple the geometry of the landscape from the topography of the representation;

- A “native” way of implementing different levels of detail;

- A natural tessellation strategy based on connecting a node to its parents (maybe you spotted it);

- Enough data to allow the landscape to be modified to produce more dramatic features across different levels of detail;

- The processes for the above should be very parallelisable.

There are still a couple of things I’m working on (3D display for a start), as I’ve been obsessing over how to organise the data structures I’m using. Hopefully I’ll be back tomorrow with some 3D views.

If you’re interested in the code you can find it here. If what you found at the end of that link didn’t make any sense to you, then you’re probably not a programmer (or you’re still learning). If you still want a look drop me a comment and I’ll see what I can do.

Disclaimer: As far as I’m aware I didn’t steel this from anybody, but I don’t claim it’s completely original, either.